DULCE LAMARCA

INTERVIEW

ISSUE I

2025Dulce Lamarca

Interdisciplinary Artist and Educator

Issue I, 2025

Excerpts of a conversation that took place on March 18th, 2025 between Ashlin Ballif and Dulce Lamarca.

Burntout (BT): Do you listen to your intuition?

Dulce Lamarca (DL): Yes, I do. When I sense it, I follow it. Once I notice it I find it hard to ignore. Nowadays, I would say intuition is the thing I trust the most. I’m still fine-tuning my ability to act on it though, as I don’t always do immediately. But what’s harder for me is recognizing and letting go of the thoughts or demands that I impose on myself. Usually it’s someone else who helps me see them. Lately, this has shown up around my studio practice. I was placing all these expectations on myself on how I “should” be working and none of it felt enjoyable or true to how I actually work. So the question became: why am I doing this? Why am I setting this expectation and demanding this for myself in the first place? Why assume things should be done a certain way anyway?

For me, art is about expressing and connecting with one’s inner world. I find the process of making art is deeply personal. But I think it should be enjoyable, you know? I want my studio and my practice to feel like a kind of playground for adults. Where if you’re not enjoying yourself, you should question yourself why so. What are you doing and in what way? Why play a game you don’t even want to play? I'd rather just play. That’s where I try to start from. And when I allow myself to do that, the process becomes enjoyable and intuitive. Creativity arises and flows organically.

BT: I guess that’s the key. Letting it be and flowing. I do think my empathy fights my intuition. Do you have a particular feeling that shows up in your body when you aren't following your intuition?

DL: Yes, it feels off. I honestly feel terrible afterwards. I think it is unhealthy not to follow your intuition. Because when you choose to ignore it, it’s like you are distrusting yourself. And that sense of self-betrayal slowly accumulates in the background. It disorients your inner compass. I’ve been there. I had to recalibrate, and that takes time. So, to me, intuition is really about being fully present, aware, and choosing to trust yourself.

BT: Sometimes I don't think about it that way, as being present, because intuition at times feels like it's this distant voice or feeling in your body that seems far away. It feels as if it’s coming from the past, if that makes sense. As if you're out of body. It’s strange, you're listening to something, which is kind of making it so you're not present when in actuality, you're in-body. You're simultaneously being more present because you're listening to yourself. And I don't know if that makes sense, but sometimes that's how I think about intuition. Like, this little voice that's trying to call to me that feels really far away. And maybe the goal is to bring it closer.

DL: That’s interesting. For me, it’s kind of the opposite. I don’t feel it distant at all, for me it comes from my center, it’s inside and in the present. Whenever I feel it, it's so close to me that if I'm not following it, I’m denying myself. But who knows where it comes from, inside or out. I think it is more about tuning into a certain frequency.

BT: I feel like I've become physically ill after a while if I'm not listening to it. It manifests itself in my body as melancholy or depression. I feel that intensely. In your work, you discuss deep emotions with humor and absurdity. For example, in your work are we trash tho? you choose to include very specific visuals of animals alongside footage of trash, as well as archival footage of a balloon festival. We get a glimpse of the animal’s perspective, of how we as humans affect their surroundings and internal emotions. The animals you chose to focus on, the rat and the cow, do they symbolize anything in particular for you?

DL: Yes, in that work I am combining two environments, New York City and a rural area in Entre Ríos, Argentina. I wanted to connect these two worlds through adding the animals’ perspectives on our urban living and its effect. To bring to our attention that through everything that happens in our daily lives, in a distant background, their lives are still going on. Even if we don’t feel connected with them or we're not aware of it at the moment and just going about our lives in New York, there is simultaneously a cow munching grass a thousand kilometers away. I wanted to give a glimpse of these seemingly far yet connected worlds, and raise awareness of simultaneity, interconnectedness, and coexistence with other species.

As far as the animal’s perspective, the cows look at us, the viewers, curiously into our eyes as if asking, “What are you all doing?” I wanted to capture and portray the contrast between the creation of garbage and the concept of consumption with the cows just chilling in their calm simplicity. For me, they remind us of how little we actually need: just air, sunlight, grass…

It is also a critique of New York and the U.S. too. My first impression of the city when I moved to New York was: “why is there so much garbage in the streets?” In New York, garbage is everywhere. In a way I think it's better, as I believe we should be surrounded by it, in an attempt to hold ourselves accountable and face what we create, deal with its impact ourselves. As when we “throw it away”, as Gregg Braden says, it really is “away from our sight, that’s all”.

Rats are part of our shared ecosystem in New York. I chose them because they are resilient creatures, often feared and overlooked. They live with our garbage, feed on our garbage, and are treated as garbage. The cow, on the other hand, is more of a personal choice for me. My father works with cattle genetics, so I grew up surrounded by bulls and cows. The footage in the piece is mine, filmed on a farm in Argentina, in the province of Entre Ríos. I just sat with my camera on and let the cows approach me.

Cows are very curious. There’s no judgment in their gaze. They just see us. In this work, I humanize them intentionally, bringing them to eye level with the viewer, as if they’re saying, “Are you seeing this that’s going on? I'm also watching, watching while munching.” That contrast is where the humor comes in, as I’m trying to highlight the absurdity with this comparison. The absurdity of how humanity is destroying what sustains us, and the animals as witnesses, are just watching.

But if I just think about these two animals as symbols, I think rats represent our fears, and cows are just gentle giants that, in the context of urban living, represent our greed for consumption (not only for meat, but milk, leather, etc).

BT: Exactly, there's something sassy about cows. Particularly in the ways they look at us, yet without judgement, they ask, “what’s happening?” with attitude and then they keep eating and going about their business. We’re just together, cohabitating. That's part of the humor in your work too, with the close ups of the cows. You edit in little glimmers of humor. In many of your videos, there are small bursts of humor. Through your visuals you ask, can you believe this? And then add in another element simultaneously. Are your works connected?

DL: Yes. Everything is connected in my practice. One thing always leads me to the next.

For example, my interest in humor led me to study improv comedy which is connected to the spontaneous way I create my video works. I will begin with a simple idea and will start a sort of what I define as ‘visual improv’, where I use that idea as a prompt for the work to unfold. I do the work in one sit-down, and it lasts as much as my inspiration lasts. Which in these cases are short simple ideas, like a firematch that’s on, lasts for a short period of time, and extincts.

Besides having the same approach, the themes in the works are connected as well. My works always comment on different aspects that touch on what I am going through internally. are we trash tho?, it’s more literal on how I was feeling about living in New York. Other works like Freezing Time or Rollercoaster explore different but related thoughts on the absurdity of our actions. They all orbit around a mix of critique, and humor.

BT: And, of course, the clock keeps going. You can't control any of it except what you do with the time, which is often to worry about time. I think there are specific moments during childhood where you realize you're getting older, if that makes sense. Then there’s a moment of panic, where you want time to stop. You learn the constant of change.

DL: Right, it’s the absurdity of knowing and still worrying. In Spanish worrying is “preocuparse”, which if you break down the word, it’s pre + ocuparse. Ocuparse means “to deal with” or “to take care of something,” so the word worrying (preocuparse) suggests this ridiculous attempt “to take care of something in advance” or “to try to resolve the issue before it even happens.”

BT: In the video, what is the significance of opening and closing the freezer door? Humor and impatience? I like the idea that every time you open the door it’s a portal, or a different place in time just because a second has gone by.

DL: Exactly. When exhibiting my work, I also become the audience of it and I remember noticing the same thing. The doors opening and closing create this sensation, acting as portals to different spaces within the exhibition space. That’s something that repeats in my work. The video performance where I am tuning the cello in an elevator for example, you experience a closed door, you hear the sound of the cello first, and then the doors open and reveal myself inside the elevator. Doors close and open, sporadically, as the freezer door in Freezing Time.

BT: Is taking space or distance from creating important to you?

DL: Si, it is a crucial part of the process for me. I believe one needs to know when to step back. I think most artists probably relate to this, whatever the medium is, painting, video… I believe taking distance is necessary. With distance comes perspective.

BT: How do you feel about your perspective shifting? New York compared to Argentina or a new place versus your hometown.

DL: Time moves differently in New York. In NY, time is money and money is time. Everything and everyone is running. Rats, people, trains… I often felt out of sync at the beginning, overwhelmed, I definitely - and proudly - come from another rhythm. Surrounded by rush, I had to constantly remind myself to keep following my own pace. What originally seemed like two years turned into seven. I now know I can navigate the city moving in sync with its pace.

I always have a hammock in my studio, as an invitation to slow down. My studio and the hammock as symbols appear in my practice as well. New York felt like a weird context for a hammock though. The ambient sound just did not match. Seemed kind of absurd, trying to slow down in a place that’s so fast, but for me it was necessary. And for others too, as I would frequently come to my studio to find an artist friend / studio neighbor napping on my hammock.

But in terms of where to be, I feel at home in both Argentina and New York. But lately, I have been experiencing a strong need for silence, a need to return to another kind of tempo and landscape. I have also realized that for my current projects and practice, I need to be physically more present in South America. As the setting and imagery of my projects have been shifting to different environments in the southern hemisphere, specifically in Argentina, Brasil, and Uruguay.

BT: This reminds me of our compass conversation, and how a compass can be a watch in some ways, intuitively. There are going to be certain times when you know it's time to leave a place, and that could be seven years or five months. It’s interesting how your body knows when it's time to move. Or when it’s time to return back to yourself or try a different way. I find that faith or trust in oneself interesting.

DL: Yes. I guess it all comes back to intuition. I had a feeling, which only grew, and I followed it. It just became clearer and clearer with time that I needed to spend more time in the southern hemisphere, so that is what I am doing for now.

BT: How does your history with hospice work inform your practice? Is it related to the theme of freezing time at all?

DL: Yes. I think my background in music, playing the cello, along with my hospice work definitely informed my practice and interest in working with time, both as a character and as material.

It is deeply related to what we talk about my Freezing Time piece. I began working at a hospice due to some personal experiences with death. These made me realize I had the facility to deal with the dying, and also gave birth to a strong feeling, an urge, a belief that no one should go through that alone. (Unless by their own choice, of course). These experiences of loss urged me to accompany people in their process of dying.

I worked for three years as a volunteer in a hospice in Buenos Aires before moving to New York. For context, the hospice is not a hospital. It is a house. With a kitchen, living room, garden, laundry room, etc, mostly run by volunteers. It hosts people that are no longer under any treatment. There, they are cared for their symptoms, assuring they can live and enjoy the best quality of life possible until the end. Contrary to what people assume when one says the word hospice, the house is full of life. Full of presence and awareness of life. There, you learn how to be fully present, without rushing. You have to. In an opposite way than New York, the hospice is a place where time sits still.

I remember being advised that if we were to enter a room [to visit a person with a terminal disease], and we were in a rush or worried about something else that we had to do right after, then we just shouldn’t go in at all. In order to go in, we had to be ready to leave time outside. If we went inside a room we had to be able to be present and not think about time. Time didn’t exist. I always cherished that advice. And I agree, it's a very delicate situation, so if you're gonna be in a rush or in a bad mood because you're worried about something, then, better not to bring that energy to the room. Working in the hospice was a very profound way of practicing consistent presence.

That presence became the core of my Tuning Series, a series of performances where I am tuning my cello without ever really starting to play. It’s about that in-between moment. The constant preparation for whatever may come. Inhabiting that space between point A and point B, where B could be death, or anything else. The work invites the audience to be patient, or feel the tension, the waiting. And in that way, it mirrors the hospice experience of learning to sit with the present.

BT: Right, worrying is not being present at all. In this work, you're actually utilizing that time to be present and focus. It's interesting thinking about how you were so scared of death and wanted to freeze time when you were younger, and then you ended up working at a hospice center.

DL: Well, I chose to work at a Hospice in the hopes to work on my relationship with death through the experience as a volunteer. I thought it could be a way to work on my relationship with time, the fear of its passing, and my own fear of death. I think my attempts to freeze time were freezing me, as I was focusing on dying and not on living. Working at a hospice was a way for me to face my fears.

BT: What are you excited about now? What are you working on currently?

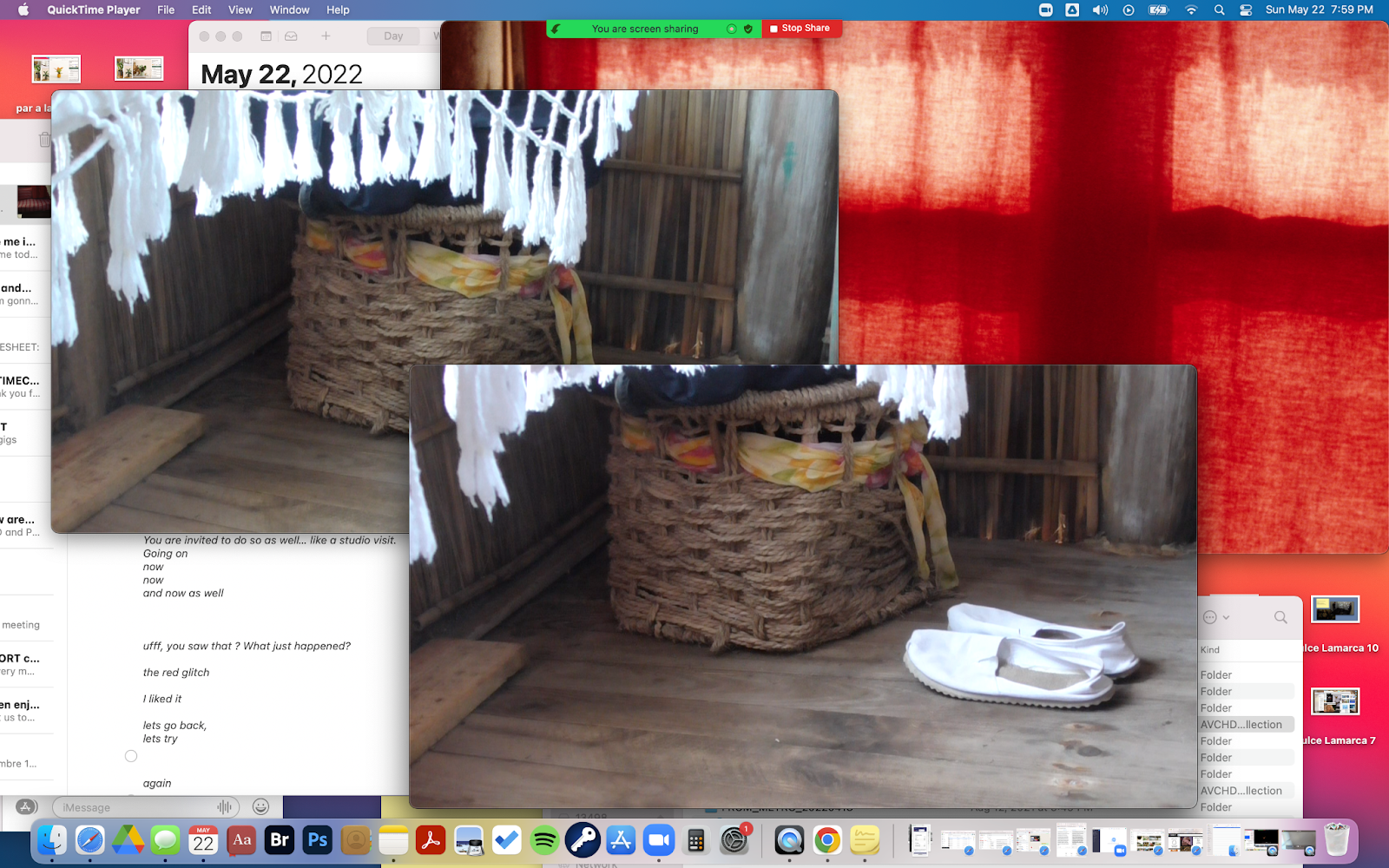

DL: I have been working on a film project since 2022. It is about a stilt house made out of wood and straw, with no electricity nor running water, that is being threatened by the sea level rising.

In 2023, I reviewed the footage for the first time with the audience during an online endurance performance titled Can you here me? I also have a limited edition of film stills printed on fabric, Leyendo is one of them.

But I took my space from the film project for a while. Right now I am excited to have a studio space again and more time for my practice. I think it is about time to fully submerge in this paused project and I am getting ready to do so.

The film I want to focus on serves as a dreamlike portrait of this place, an old person, and an animal. It portrays how they co-inhabit in that environment. It’s an invitation to raise awareness on our interconnectedness and a meditation on how we live our lives.

My most recent work is a video performance where I record myself measuring the distance from the house to the sea with my steps. The piece is titled 50 Mts, it will be part of Bodies and Borders: Ecologies of Consent, a juried group exhibition at WEAD, Georgia, U.S from October 1, 2025 to January 31, 2026. I plan to keep doing this performance over the years.

Dulce Lamarca is an Argentinian-born interdisciplinary artist and educator living and working between Buenos Aires and New York. Her practice explores different ways of perceiving time and evokes a sense of introspection about how we live our lives. Informed by her background as a cellist and her years working in hospice care, she engages themes of transience, longing, and belonging through video installations and participatory performances, often using humor, technology, and collective presence as central tools.

Her current work focuses on material consumption and our relationship with the environment, reflecting on the consequences of urban living, overconsumption, and ecological degradation, as well as our interconnectedness with other species and with one another.

Lamarca holds a BFA from Regina Espacio de Arte (Buenos Aires) and an MFA from the School of Visual Arts (New York). She has also completed specialized training in doula work, photography, art therapy, improvisation, and end-of-life care. She currently volunteers with Fundación Sí’s Recorridas Nocturnas, a nightly outreach program for people living on the streets.

Her work has been exhibited internationally across the Americas, Europe, Asia, and Oceania, and has been featured in Terremoto, Art & Education, TEDx Taiwan, and the Otago Daily Times, among others.